The Licentious Life and Times of Jann Wenner

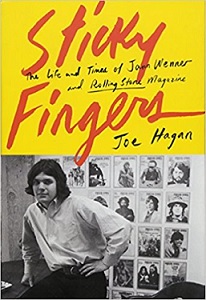

New York Times Book Review, November 27, 2017 Book ReviewsSticky Fingers: The Life and Times of Jann Wenner and Rolling Stone Magazine, by Joe Hagan. 560 pp. Alfred A. Knopf. $29.95.

Joe Hagan paints the rogue's life of the Rolling Stone co-founder Jann Wenner with a brush made of stinging nettles, rasping the famed editor's reputation on nearly every page. Wenner betrays. Wenner lies. Wenner cheats. He reneges on promises. He sucks up to stars, letting them approve copy in his magazine. Stealing a book-editing credit from an underling, he justifies it as "a 'droit du seigneur' thing."

Joe Hagan paints the rogue's life of the Rolling Stone co-founder Jann Wenner with a brush made of stinging nettles, rasping the famed editor's reputation on nearly every page. Wenner betrays. Wenner lies. Wenner cheats. He reneges on promises. He sucks up to stars, letting them approve copy in his magazine. Stealing a book-editing credit from an underling, he justifies it as "a 'droit du seigneur' thing."

"He leads with his appetites--I take, I see, I have," says Art Garfunkel, who knows him well, capturing the mogul's method in a tidy tricolon. "I don't know how he does it, but I think he's pretty much immune to guilt," adds Tom Wolfe, who thrived under his direction in the 1970s and '80s.

Indictments like these would shatter an ordinary man into crushed stone. But Wenner's narcissistic and violent temperament, on high boil since early youth and on full display in this survey of his life, has made him impervious to outside judgment. He's one part Sammy Glick, using and discarding people on his race to the top. He's a shot of Richard III, cruel and controlling. And he's a lot like Mr. Toad, singing self-praise at every available turn. But don't worry: The book's cutting assessment won't cause him any more pain than a brisk, full-body dermabrasion.

Hagan comes to bury his real-life antihero. Given the critical material--seven decades' worth--he has to. But Hagan also lavishes praise upon Wenner for building a media empire from a tiny grubstake. That Wenner has been liquidating his empire--Rolling Stone was put up for sale as Sticky Fingers went to press--only makes the story more urgent. When they build a pantheon of scamps-turned-great publishers, a plaster bust of Wenner will stand next to the men whose careers inspired him: Hugh Hefner, Henry Luce and William Randolph Hearst.

Born in 1946 during the opening hours of the baby boom (his first pediatrician was Dr. Benjamin Spock), the young Wenner was "short and pudgy, with a prickly intelligence and a bracing self-confidence." He was also a bad person, according to the early assessments. "A pain in the ass," his father said. "He can be, and frequently is, extremely cruel to his classmates," one boarding school teacher reported. Wenner claims that following their divorce, his mother and father "fought over not who got to keep Jan Simon Wenner but who had to take him." He even swears his bohemian mother once called him "the worst child she had ever met."

No surprise, then, that Wenner's pushy press mogul persona surfaced in his youth. At the age of 11, he joined two neighborhood kids who had started a mimeographed newspaper and shoved his way to the editor in chief position. Later, when his broken family abandoned him to a Southern California boarding school overstocked with the offspring of celebrities (Jack Benny, Yul Brynner, Judy Garland et al.), he used the school yearbook and the underground newspaper he founded (The Sardine) to climb the social ladder. The ability and willingness to ingratiate himself to others would prove indispensable into adulthood as he charmed new investors or flattered rockers, movie stars, politicians and the wealthy to appear in his pages.

Studying at Berkeley, Wenner collected the other seeds that would sprout into Rolling Stone. Devoted to LSD, he became the campus newspaper's drugs and rock correspondent, plunging into the Merry Pranksters scene Tom Wolfe describes in "The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test." He adopted the experienced jazz writer Ralph J. Gleason as his mentor, and eventually co-founded Rolling Stone with him. A visit to the London offices of Melody Maker added to his growing vision: Here was a serious newsroom filled with professionals covering music, not a grubby underground paper produced by a commune. He saw. He wanted. He would make.

New publications have a way of rising from the ruins of others. Rolling Stone owes much to The Sunday Ramparts, the short-lived biweekly paper spun off from Warren Hinckle's Ramparts magazine. Wenner, who joined the staff in 1966 to cover culture, lifted its graceful design after it folded in 1967. Fusing all he had observed about the trade press, fan rags, criticism and feature writing into one, and drawing on competing underground journals like Crawdaddy! and Mojo Navigator, he created Rolling Stone on a shoestring. "It's just so good," Wenner wept as the first copy rolled off the press.

Until Rolling Stone appeared, young readers had been either dismissed or ignored by existing media. Graybeards will tell you that those early pages were almost a cultural revelation, exciting them to the potential of print the way the web would stimulate a future generation. Hagan reckons that "from 1971 to 1977, Jann Wenner was the most important magazine editor in America." Who can disagree? (Disclosures: Three decades ago, Rolling Stone paid me a kill fee for an assignment I botched. Hagan is a casual acquaintance with whom I've made small talk on Twitter. About five years ago we talked briefly about his Wenner project and other topics over coffee.)

Hagan, whom Wenner personally asked to write his biography over lunch in 2013, swings the biographer's baton with authority, telling Rolling Stone's story while capturing Wenner in all his ragged glory. "He was an antiwar liberal and a rapacious capitalist, naive and crafty, friend and enemy, straight and gay, editor and publisher," Hagan writes. Sticky Fingers excels in conveying the complexity of the most intimate and least covered part of Wenner's life: his sexuality. Wenner's homosexual drive, first expressed in "ambiguous horseplay" that got him arrested at the age of 12, was not fulfilled in what he considered a full-fledged "romance" until 1967, when he was 21. He remained on the down-low for the better part of 30 years, fearing he would be outed. His wife, the elegant and alluring Jane Schindelheim--they met while she was a receptionist at Sunday Ramparts and her family became a founding investor in his magazine--responded to his affairs with her own. "She didn't make me feel guilty; she let me off the hook every single time," Wenner tells Hagan.

Wenner officially came out in 1995, leaving Jane for a man with whom he eventually made a family. A tincture of Wenner's gayish sensibility was always on display in the magazine if you looked for it. The Cockettes drag troupe got early, sympathetic coverage in 1971 and, as Wenner has long acknowledged, the come-hither photographs of androgynous performers like Mick Jagger weren't exclusively for the ladies. "That was very gay," Wenner now concedes of a 1973 illustration of the Olympic swimmer Mark Spitz, imagining him as a Vargas boy. The same goes for the glimpse of David Cassidy's pubic hair in a shot by Rolling Stone stalwart Annie Leibovitz, published in 1972. In the afterword, Hagan writes that Wenner gave him free rein but asked for the chance to review the "most deeply personal matters--namely, his sex life." Wenner turns out to be no censor. The book teems with his endless pairings and hints at threesomes. One blushes imagining what Wenner asked to be deleted.

Sticky Fingers makes excellent use of the dozens of hours of interviews Wenner gave him along with 500 boxes of notes, pictures, postcards, recordings, correspondence and other material Wenner started saving at an early age in anticipation of this very biography. Wenner so treasured these archives that he stored them in a vault for safekeeping during the Three Mile Island meltdown. Hagan never locates Wenner's Rosebud in the hoard, but comes ever so close to writing his Citizen Kane.