Ben Bradlee's Charisma Trick

Washingtonian, December 2017 Magazine Work

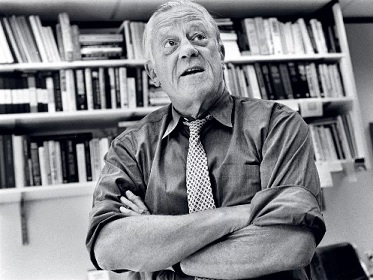

Ben Bradlee hasn't shone this brightly since the 1970s, when he stared down the Nixon administration over the Pentagon Papers and won, led a tireless staff to produce momentous Watergate coverage, and came to represent the epitome of the ballsy newspaper editor in the public imagination. Buried just three years ago at age 93, Bradlee is being resurrected by Steven Spielberg in a new Pentagon Papers docudrama, The Post (opening in limited release December 22), and by HBO in a documentary titled The Newspaperman: The Life and Times of Ben Bradlee (airing December 4). There's also a new edition of his 1995 autobiography, A Good Life, with a fresh introduction by Watergate's Glimmer Twins, Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, and an afterword by his wife, Sally Quinn. If the Commission of Fine Arts ever decides to build a national monument honoring journalists, it will probably order a grinning sculpture of Bradlee, his shirtsleeves rolled up to expose forearms that would shame Popeye.

Why do we revere Bradlee but barely remember Abe Rosenthal, the New York Times editor who was his contemporary and equal? Rosenthal published from the Pentagon Papers first. (The Post got into the fray after a federal court told the Times to stop.) And Rosenthal's innovations—introducing freestanding sections devoted to metro, lifestyle, and other subjects—did as much to reinvent the daily newspaper as Bradlee's did. But Rosenthal lacked Bradlee's incandescent personality, his irrepressible charisma. People who met the Post editor were awed by his presence, with some in the newsroom imitating his sartorial style, his wisecracking, and the sailor's strut he used to exhort his reporters to greatness. Times staffers may have wanted Rosenthal's job, but they didn't want to be him.

Aside from charisma, Rosenthal lacks another legacy-fixer: No Hollywood director romanticized his persona the way Alan J. Pakula did Bradlee's in the 1976 film adaptation of All the President's Men. (One doubts that even Spielberg could make Rosenthal likable without some heavy fictionalizing.) Pakula's movie worked as an amplifier to blast Bradlee's quintessence around the universe and through time. Without it, he'd be remembered but surely not canonized. The Post's current pilot, Marty Baron, got the Hollywood treatment in 2015's Spotlight. But while he's at least as skilled an editor as Bradlee was, he doesn't have the jazz that catapulted Bradlee to the ranks of journalistic royalty.

Bradlee possessed a convivial grin, ever-attentive eyes and ears, and a hydraulic handshake, all of which added to his appeal. But his life touched other, important stations of the cross. He drew his secret knowledge of how the world works from his upper-class upbringing and Harvard education, his experience as an officer during the big war, the lessons learned from a postwar tour of duty as a Post reporter, and the diplomatic training drilled into him as a press attaché at the US Embassy in Paris.

By the time he returned to journalism with a Paris job at Newsweek, Bradlee had become his full cussed self. Even when he was the oldest guy in the room, he seemed the youngest. The charisma cookbook insists on the successful melding of opposite attributes, and on this point Bradlee excelled. He was both aristocratic and streetwise, fluent in French but as crude as a truck driver, dictatorial yet benevolent, warm and outgoing yet capable of nastiness, such as the time he ripped a pesky critic in a letter, calling him a "retromingent vigilante" (a retromingent animal urinates backward).

It would be easy to interpret the Bradlee revival as a response to the current political moment, a bit of rah-rah for the besieged press. But the comparison doesn't work. President Trump's trash talk about "fake news" has yet to approach the hostilities unleashed by Nixon during the Pentagon Papers case. And not to take anything away from Bradlee and Post publisher Katharine Graham, but the undeniably heroic figure in the Pentagon Papers episode is leaker Daniel Ellsberg, who risked spending the rest of his life in prison. Nor were the Times and the Post the only newspapers to act courageously. The Boston Globe began publishing from the documents three days after a court order blocked the Post, and others followed.

Pop culture's investment in the Bradlee legend has only deepened since All the President's Men, with Spielberg's movie paying the latest dividend. Bradlee has now assumed the position of proxy whenever we think of a crusading, cussing, well-dressed editor. In the movies, editors tend to act like Bradlee, even if they're not named Bradlee.

Another key to the Bradlee myth is Katharine Graham, played in The Post by Meryl Streep. (The less said about Spielberg's casting of everyman Tom Hanks as Bradlee, the better.) The rom-com tension between Bradlee and his boss, based on genuine affection but sometimes clashing views on how to run the paper, made them ideal office spouses. "Damn it, Katharine," he famously bellowed at her early criticisms of the Style section that he'd created, "get your finger out of my eye." As noted, charisma works best when accentuating contrast. Graham over-advertised her self-doubts; Bradlee never appeared to have any. As a willing accessory to Bradlee's daring, Graham offered a feminine dimension against which a tick-tock about Abe Rosenthal and Arthur Ochs "Punch" Sulzberger could never compete.

According to Sally Quinn, Bradlee wasn't an introspective man. He avoided what he called "navel-gazing," preferring to explore life's exteriors. She concedes in her afterword to A Good Life that in the "last few years after Watergate he just didn't have the same passion for his work." This abdication seems to have neither harmed his reputation nor erased him from the collective consciousness. He retired from the newsroom at 70 in 1991 but remained a focus of attention even as dementia began to crimp his boulevardier style. While his lights dimmed, his eyes still gleamed and small crowds that craved his bad-boy leadership continued to flock around him.

Many of us refuse to release Bradlee because, on some level, we still want to be him. He's Washington's living ghost, charming us with his wisecracks, dazzling us with his sartorial style, exhorting bravery, and daring us to tap our inner scoundrels.