Matt Bai’s ‘All the Truth Is Out,’ About Gary Hart

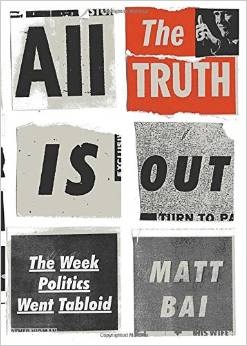

New York Times, Oct. 31, 2014 Book ReviewsAll the Truth Is Out: The Week Politics Went Tabloid, by Matt Bai. 263 pp. Alfred A. Knopf. $26.95.

"This whole business of '87 is flypaper to me," Gary Hart said. "I want to get unstuck."

"This whole business of '87 is flypaper to me," Gary Hart said. "I want to get unstuck."

Hart's self-image — of being glued to a pest-strip and pleading for release — remains accurate, even though he offered it in an interview a dozen years ago. He had been the front-runner in the Democratic Party's 1988 presidential campaign, but then the Miami Herald responded to an anonymous tip that Hart — a married man — was having an affair. The newspaper's reporters staked out his Capitol Hill home and discovered his friendship, possibly intimate, with a young woman named Donna Rice. Hart and Rice admitted to no wrongdoing, with Rice saying "no" three separate times when asked if she and Hart had had "sexual relations." Although both insisted that the press had no right to invade their privacy with its questioning, the media typhoon pounded the two, washing Hart out of the race and into political limbo, where he languishes today.

Hart seems resigned to his status. Otherwise he probably wouldn't have cooperated with Matt Bai, a former New York Times Magazine reporter, who examines the episode and its impact on the press and politics in All the Truth Is Out. Bai writes about Hart's terrible year with empathy, calling his "humiliation ... the first in a seemingly endless parade of exaggerated scandals and public floggings," denying the political process the best and the brightest.

Reporters had previously ignored the extramural sexual adventures of such presidents as Kennedy and Johnson, so where did they get off targeting Hart's personal life? Bai, who collected Hart's flypaper complaint for a 2003 Times profile, concedes that Hart did himself no favors in his handling of the press, but he expresses his deepest disdain for the reporters who carried "political journalism into dark and unexplored waters." To his credit, even though Bai admires Hart and thinks he got a raw deal, he doesn't stack the deck, allowing readers to consider the evidence and acquit or convict as they see fit.

An unspoken rule of Washington political coverage had long dictated that a politician's sexual dalliances could be ignored as long as he remained circumspect about them. Only when embarrassing moments in a politician's personal life became too public to overlook — as in 1974 when the police pulled Representative Wilbur Mills's weaving car over and a stripper leapt out, or in 1976 when a "secretary" blabbed to reporters that Representative Wayne Hays had placed her on his staff payroll to provide him with sexual services — would the press serve up sexual dirt.

This unspoken rule was still intact when Hart commenced his second run for the presidency in April 1987. "It was well known around Washington, or at least well accepted, that Hart liked women, and that not all the women he liked were his wife," Bai writes. Hart and his wife, Lee, had previously separated twice, prompting a 1984 Washington Post reference to their "on-again, off-again marriage that has become a whispered campaign issue." By 1987, the Washington columnist Jack Germond was telling Hart, whom he had befriended, that he didn't care whom Hart slept with, but that his "zipper problem" was out there. Hart, like Kennedy and Johnson before him, was aware that reporters either knew of or suspected his liaisons, but apparently assumed they would abide by the old conventions.

Right after Hart entered the 1988 race, Newsweek and the New York Post added renewed speculation to the rumors. And when an anonymous tipster made new claims about an active affair, Tom Fiedler, a political reporter for the Miami Herald, and his Herald colleagues chased down those clues, instituting the Washington stakeout. The press never proved that Hart and Rice had consummated their relationship, but the abundance of circumstantial evidence uncovered, the press grilling of Hart and a pending Washington Post story linking Hart to yet another woman spelled his political end.

In reviving the episode, Bai re-examines some high-profile elements from it that most misremember, elements that still shape the way we think of 1987. The most notable of these is Hart's seemingly brazen gauntlet-toss at the press about his alleged womanizing. "Follow me around, I don't care," Hart told E. J. Dionne of the New York Times Magazine>. But because the comment wasn't published until after the Herald had already encircled Hart's place, nobody can claim that the Herald was simply accepting his dare. So, yes, Hart dared the press corps to trail him. And yes, he even sanctioned its snooping with words like "I don't care." But no, the Herald didn't accept Hart's dare because it had not yet heard it.

How to judge the Herald is a question at the heart of Bai's book. Bai gives it to the paper and other journalists hard for turning the 1987 campaign into a circus, as "the finest political journalists of a generation surrendered all at once to the idea that politics had become another form of celebrity-driven entertainment, while simultaneously disdaining the kind of reporting that such a thirst for entertainment made necessary." Such sensationalism, he holds, has deterred politicians from speaking their minds to the press lest they expose an unflattering part of their personality or make a gaffe.

Bai also affixes blame to technology for the Hart conflagration, 1987 being the year that the proliferation of satellite TV trucks, lightweight videotape cameras, fax machines and portable PCs accelerated the news in a way that has robbed the press of the time needed to properly assess coverage.

This argument was made, of course, every time a faster printing press was installed, when the telegraph was invented, when the telephone became commonplace, when radio and then television arrived, when bloggers came on the scene, when smartphones became ubiquitous. It's probably true that hastened metabolism can spoil news stories, but the press has a way of taming technological advances to the advantage of the reader. I doubt many journalists or news consumers would press a button to go back to 1982 if they could.

Instead of accepting Bai's proposition that the flypaper year of 1987 was a watershed moment in journalism, perhaps we should think of Gary Hart as a watershed candidate. His insistence on running an aloof, on-his-own-terms campaign for president raised questions wherever he went. He refused to pose for press portraits, refused to answer reporters' questions about polls and strategy, Bai writes, and came off as arrogant and self-important to reporters. Hart was such a loner that few of his Senate colleagues rose to support him. The Washington Post editorial board was impressed by Hart's substantive ideas, but still had trepidations about him, stating in an editorial before the blowup, "Ideas are not all there is to a campaign: human beings choose which ideas will govern. And there apparently still is some unease with Gary Hart the person."

If Hart's political crackup ended the coziness between politicians and the press, perhaps it's something we can celebrate as well as lament. Washington reporters respected Hart's personal privacy year after year, as Bai reports, with one journalist, Bob Woodward, growing so close to him that he allowed Hart to officially bunk at his house during his first marital separation (in truth, Hart was spending most of his time at a girlfriend's place). There's a thin line between a journalist respecting a politician's privacy and covering for him, and shacking up with one definitely crosses it. Whether or not you think the press should nose around in politicians' sex lives, the fact that Hart was ultimately undone by reporters from outside the New York-Washington corridor indicates that the political press might have become too captive for its own good.

Returning to the story with fresh eyes, Bai has produced a miniclassic of political history that will restart the debate of 1987. But that debate will forever leave Gary Hart writhing in its grip.