King of the Hill: The life of Scotty Reston.

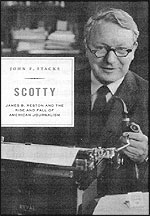

Washington Post, Jan. 5, 2003 Book ReviewsScotty: James B. Reston and the Rise And Fall of American Journalism, by John F. Stacks, Little Brown. 372 pp. $29.95

Before writing this review, I polled a bunch of under-40 journalists to determine their familiarity with such legends of the journalistic craft as H.L. Mencken, Damon Runyon, Ernie Pyle, Walter Winchell and I.F. Stone. Most of my respondents could identify these journalists, with a good number having read something by or about them.

But nearly all were flummoxed by the name James B. Reston. Those who knew his name--most didn't--connected him to the New York Times, where he worked for almost four decades. But beyond that they were stumped.

That Scotty Reston, former king of Washington journalism and founding member of the commentariat, should be so forgotten just seven years after his death is surprising. John F. Stacks's comprehensive biography, Scotty, will surely rectify that oversight--but not in a way that will please the pundit's ghost. Although Stacks treats his subject generously, calling him the "best reporter in Washington" in the 1950s, he judges Reston "a shill and an apologist" for powerful politicians, "the personification of what the true journalist should not be."

Reston practiced the sort of crony journalism that better served sources such as Dean Acheson, John Foster Dulles, John F. Kennedy and Henry Kissinger than it did readers. An accomplished back scratcher, Reston imagined himself a Washington player, a journalist diplomat and a senior member of the fourth branch of government--and by the rules honored during those times, he was.

James Reston was born in 1909 and immigrated to the United States twice from Scotland with his family, once as a toddler and again as an adolescent, before his working-class clan took root in Dayton, Ohio. The young Reston parlayed a sweet golf swing into a friendship with James Middleton Cox, the newspaper publisher and governor of Ohio who had been a losing presidential candidate in 1920 (Franklin Roosevelt was on the bottom of his Democratic ticket). Cox lent Reston college money, and after the student sportswriter graduated from the University of Illinois, Cox gave him a job at his Springfield, Ohio, paper. After stints as a university sports department flack and a gofer for the Cincinnati Reds, he joined the Associated Press in New York City as a feature writer.

Even then, though, the ambitious Reston had the New York Times in his sights. In 1937, the AP sent him to London, where he charmed the Times bureau chief into giving him a job in 1939. It was a fabulous assignment, and Stacks gives Reston good marks for his coverage of the Blitz and the House of Commons. In his first and perhaps last act of journalistic iconoclasm, Reston and his Times colleagues bravely violated British censorship rules to report a German submarine attack on a Scottish port.

When the 31-year-old Reston took ill, the Times sent him back to New York, where he applied his charms to the Sulzberger family, the paper's owners. His bond with publisher Arthur Hays Sulzberger and his wife, Times heiress Iphigene Ochs Sulzberger, grew so tight so quickly that his enemies took to calling him the "adopted Sulzberger." The rich and powerful are so accustomed to fending off suck-up artists that, whenever one penetrates their ramparts, we know we're dealing with a special talent. In quick order, the young Reston was writing speeches for Sulzberger and accompanying him on a fact-finding world tour.

In his memoirs, Reston acknowledges that other newsroom hands considered him Sulzberger's spy--which, of course, he was. By the time of Reston's second posting to the Times Washington bureau, in 1944, Sulzberger granted him his own franchise, independent of the bureau chief.

In those years, when the federal government had yet to swell to its present gargantuan proportions, the Washington press corps was a tiny, obedient thing--"a clubby little band of rather uneducated hacks," Stacks calls them--who massaged press releases into news. Times correspondents were no different, playing cards all day and rewriting AP dispatches by deadline and calling it a day. "The press largely accepted what was told them, reporting it as fact," Stacks writes. As hard as it may be to imagine now, the press was content to distribute official news from Washington authorities to the rest of the country. Not only were there no boat rockers, there was no boat to rock.

Into this vacuum entered Reston. He sized up the right people to flatter and befriend, notably pundits Walter Lippmann (a syndicated columnist), David Lawrence of U.S. News & World Report and the Alsop brothers, Stewart and Joseph, as well as Washington Post publishers Philip and Katharine Graham. With them he formed a kind of press cartel, defining what was news and, more important, what wasn't. Later, when John F. Kennedy was president, Reston the bureau chief spiked the investigations of a reporter who was looking into rumors that JFK had been married before taking Jacqueline Bouvier as his wife. "I will not have the New York Times muckraking the president of the United States!" Reston erupted. After Lyndon Johnson took over the White House, Reston discouraged his reporters from following the influence-peddling scandal surrounding longtime Johnson aide Bobby Baker lest it weaken the new president.

Reston became the "master of soft soap" in Washington, Stacks writes, building relationships of trust with insiders. "They saw Reston as someone outside the political process to whom they could talk candidly, but at the same time a knowledgeable player in the political game who would understand their trials and dilemmas."

Into such a willing vessel flowed scoop after scoop, mostly in the form of "calculated leaks," official documents given to reporters by high officials to move the news in their direction. Reston's first Pulitzer Prize came in 1945, when he was leaked (by an old acquaintance) sensitive documents from a conference founding the United Nations, which were then published. A couple of years later, Reston helped Sen. Arthur Vandenberg rewrite a speech in which the isolationist refashioned himself an internationalist. By comparison, the controversial letter of advice that Fox News boss Roger Ailes sent President Bush in the immediate aftermath of the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks looks completely innocent.

Reston continued to befriend such wise men of Washington as Dean Acheson and John Foster Dulles, whose aide gave him secret papers from the Yalta conference. They knew they could rely on him to present their agendas judiciously when they offered him calculated leaks of information. Although Stacks calls Reston "the best reporter in Washington" in the '50s, he is being too kind. To paraphrase Truman Capote, what he did wasn't reporting; it was typing. During that decade there were dozens of major stories that should have been told but weren't because gatekeepers like Reston were too busy guarding the reputations of their important sources. The CIA was mounting coups in Guatemala and Iran and testing mind-control drugs on the unsuspecting. The government deliberately poisoned hundreds in radiation experiments. Foreign policy by assassination was the rule. J. Edgar Hoover's FBI built dossiers on thousands, including politicians and civil rights leaders. Hoover didn't beat the Washington press with his stick; he kept them in line by dispensing carrots from the dossiers that willing reporters turned into news.

Perhaps Reston's undeniable accomplishment from those years was his knack for discovering and nurturing talent through his clerks system, through whose ranks walked Jonathan Yardley, Donald Graham (yes, that Donald Graham), Steven Roberts, Craig R. Whitney, Matthew Wald, David K. Shipler, Linda Greenhouse, Steven Rattner and others who would make journalistic names for themselves.

Finally, Stacks reports, it was television that broke Reston's grip on Washington journalism. As the TV hordes arrived to broadcast JFK's press conferences, Reston bawled that the press corps "no longer cover the President; they smother him." By virtue of the confidence Kennedy had in Reston, he continued to score his official coups, withholding important information if asked. But the news cartel was toppling. Too many new voices were joining the mix, and the many lies peddled by the pliant press had made the public forever skeptical of the government and of Restonized journalism. It's slightly pathetic to read Stacks's account of Reston lecturing Kennedy press secretary Pierre Salinger on how important it was for the White House to place its calculated leaks in the Times, or of Reston telling President Johnson through an intermediary that as long as he and Lippmann supported the president the rest of the Washington press corps would fall into line.

By the end of the '60s, Reston's prejudices were so wedded to power that when Sen. Edward Kennedy drove Mary Jo Kopechne to her watery grave in Chappaquiddick, Reston, who was staying at his summer home on Martha's Vineyard, dictated this lead to the Times, oblivious to who the real victim of the crash was: "Tragedy has again struck the Kennedy family." The Times had the good sense to bury the sentence deeper in the story, Stacks reports.

The cartel finally collapsed when Richard Nixon was elected president. Stacks attributes its demise to the erosion of trust between government and the press brought on by the Vietnam War, the Pentagon Papers and Watergate, but it probably has as much to do with the emergence of investigative reporters such as Seymour Hersh, Jack Anderson and Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, who eagerly took on the Washington sacred cows the cartel protected. I think we're better off with the current adversarial relationship, which is poisonous and cynical, but also honest. When the cartel broke up, we learned exactly how great a reporter Reston really was. As a liberal centrist, he had always fared best with handouts from Democrats, but the Nixon establishment had no regard for Team Reston or interest in winning good press from the Times or anybody else--with one exception: Henry Kissinger, whose "manipulations" of fact, as Stacks calls them, the alleged "best reporter in Washington" dutifully and repeatedly published.

Rather than take umbrage, Reston asked Kissinger to write him a dust-jacket blurb for his 1991 memoir. Henry was only too happy to scratch Scotty's back one more time. Small wonder that Reston has been forgotten.

Before writing this review, I polled a bunch of under-40 journalists to determine their familiarity with such legends of the journalistic craft as H.L. Mencken, Damon Runyon, Ernie Pyle, Walter Winchell and I.F. Stone. Most of my respondents could identify these journalists, with a good number having read something by or about them.

But nearly all were flummoxed by the name James B. Reston. Those who knew his name--most didn't--connected him to the New York Times, where he worked for almost four decades. But beyond that they were stumped.

That Scotty Reston, former king of Washington journalism and founding member of the commentariat, should be so forgotten just seven years after his death is surprising. John F. Stacks's comprehensive biography, Scotty, will surely rectify that oversight--but not in a way that will please the pundit's ghost. Although Stacks treats his subject generously, calling him the "best reporter in Washington" in the 1950s, he judges Reston "a shill and an apologist" for powerful politicians, "the personification of what the true journalist should not be."

Reston practiced the sort of crony journalism that better served sources such as Dean Acheson, John Foster Dulles, John F. Kennedy and Henry Kissinger than it did readers. An accomplished back scratcher, Reston imagined himself a Washington player, a journalist diplomat and a senior member of the fourth branch of government--and by the rules honored during those times, he was.

James Reston was born in 1909 and immigrated to the United States twice from Scotland with his family, once as a toddler and again as an adolescent, before his working-class clan took root in Dayton, Ohio. The young Reston parlayed a sweet golf swing into a friendship with James Middleton Cox, the newspaper publisher and governor of Ohio who had been a losing presidential candidate in 1920 (Franklin Roosevelt was on the bottom of his Democratic ticket). Cox lent Reston college money, and after the student sportswriter graduated from the University of Illinois, Cox gave him a job at his Springfield, Ohio, paper. After stints as a university sports department flack and a gofer for the Cincinnati Reds, he joined the Associated Press in New York City as a feature writer.

Even then, though, the ambitious Reston had the New York Times in his sights. In 1937, the AP sent him to London, where he charmed the Times bureau chief into giving him a job in 1939. It was a fabulous assignment, and Stacks gives Reston good marks for his coverage of the Blitz and the House of Commons. In his first and perhaps last act of journalistic iconoclasm, Reston and his Times colleagues bravely violated British censorship rules to report a German submarine attack on a Scottish port.

When the 31-year-old Reston took ill, the Times sent him back to New York, where he applied his charms to the Sulzberger family, the paper's owners. His bond with publisher Arthur Hays Sulzberger and his wife, Times heiress Iphigene Ochs Sulzberger, grew so tight so quickly that his enemies took to calling him the "adopted Sulzberger." The rich and powerful are so accustomed to fending off suck-up artists that, whenever one penetrates their ramparts, we know we're dealing with a special talent. In quick order, the young Reston was writing speeches for Sulzberger and accompanying him on a fact-finding world tour.

In his memoirs, Reston acknowledges that other newsroom hands considered him Sulzberger's spy--which, of course, he was. By the time of Reston's second posting to the Times Washington bureau, in 1944, Sulzberger granted him his own franchise, independent of the bureau chief.

In those years, when the federal government had yet to swell to its present gargantuan proportions, the Washington press corps was a tiny, obedient thing--"a clubby little band of rather uneducated hacks," Stacks calls them--who massaged press releases into news. Times correspondents were no different, playing cards all day and rewriting AP dispatches by deadline and calling it a day. "The press largely accepted what was told them, reporting it as fact," Stacks writes. As hard as it may be to imagine now, the press was content to distribute official news from Washington authorities to the rest of the country. Not only were there no boat rockers, there was no boat to rock.

Into this vacuum entered Reston. He sized up the right people to flatter and befriend, notably pundits Walter Lippmann (a syndicated columnist), David Lawrence of U.S. News & World Report and the Alsop brothers, Stewart and Joseph, as well as Washington Post publishers Philip and Katharine Graham. With them he formed a kind of press cartel, defining what was news and, more important, what wasn't. Later, when John F. Kennedy was president, Reston the bureau chief spiked the investigations of a reporter who was looking into rumors that JFK had been married before taking Jacqueline Bouvier as his wife. "I will not have the New York Times muckraking the president of the United States!" Reston erupted. After Lyndon Johnson took over the White House, Reston discouraged his reporters from following the influence-peddling scandal surrounding longtime Johnson aide Bobby Baker lest it weaken the new president.

Reston became the "master of soft soap" in Washington, Stacks writes, building relationships of trust with insiders. "They saw Reston as someone outside the political process to whom they could talk candidly, but at the same time a knowledgeable player in the political game who would understand their trials and dilemmas."

Into such a willing vessel flowed scoop after scoop, mostly in the form of "calculated leaks," official documents given to reporters by high officials to move the news in their direction. Reston's first Pulitzer Prize came in 1945, when he was leaked (by an old acquaintance) sensitive documents from a conference founding the United Nations, which were then published. A couple of years later, Reston helped Sen. Arthur Vandenberg rewrite a speech in which the isolationist refashioned himself an internationalist. By comparison, the controversial letter of advice that Fox News boss Roger Ailes sent President Bush in the immediate aftermath of the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks looks completely innocent.

Reston continued to befriend such wise men of Washington as Dean Acheson and John Foster Dulles, whose aide gave him secret papers from the Yalta conference. They knew they could rely on him to present their agendas judiciously when they offered him calculated leaks of information. Although Stacks calls Reston "the best reporter in Washington" in the '50s, he is being too kind. To paraphrase Truman Capote, what he did wasn't reporting; it was typing. During that decade there were dozens of major stories that should have been told but weren't because gatekeepers like Reston were too busy guarding the reputations of their important sources. The CIA was mounting coups in Guatemala and Iran and testing mind-control drugs on the unsuspecting. The government deliberately poisoned hundreds in radiation experiments. Foreign policy by assassination was the rule. J. Edgar Hoover's FBI built dossiers on thousands, including politicians and civil rights leaders. Hoover didn't beat the Washington press with his stick; he kept them in line by dispensing carrots from the dossiers that willing reporters turned into news.

Perhaps Reston's undeniable accomplishment from those years was his knack for discovering and nurturing talent through his clerks system, through whose ranks walked Jonathan Yardley, Donald Graham (yes, that Donald Graham), Steven Roberts, Craig R. Whitney, Matthew Wald, David K. Shipler, Linda Greenhouse, Steven Rattner and others who would make journalistic names for themselves.

Finally, Stacks reports, it was television that broke Reston's grip on Washington journalism. As the TV hordes arrived to broadcast JFK's press conferences, Reston bawled that the press corps "no longer cover the President; they smother him." By virtue of the confidence Kennedy had in Reston, he continued to score his official coups, withholding important information if asked. But the news cartel was toppling. Too many new voices were joining the mix, and the many lies peddled by the pliant press had made the public forever skeptical of the government and of Restonized journalism. It's slightly pathetic to read Stacks's account of Reston lecturing Kennedy press secretary Pierre Salinger on how important it was for the White House to place its calculated leaks in the Times, or of Reston telling President Johnson through an intermediary that as long as he and Lippmann supported the president the rest of the Washington press corps would fall into line.

By the end of the '60s, Reston's prejudices were so wedded to power that when Sen. Edward Kennedy drove Mary Jo Kopechne to her watery grave in Chappaquiddick, Reston, who was staying at his summer home on Martha's Vineyard, dictated this lead to the Times, oblivious to who the real victim of the crash was: "Tragedy has again struck the Kennedy family." The Times had the good sense to bury the sentence deeper in the story, Stacks reports.

The cartel finally collapsed when Richard Nixon was elected president. Stacks attributes its demise to the erosion of trust between government and the press brought on by the Vietnam War, the Pentagon Papers and Watergate, but it probably has as much to do with the emergence of investigative reporters such as Seymour Hersh, Jack Anderson and Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, who eagerly took on the Washington sacred cows the cartel protected. I think we're better off with the current adversarial relationship, which is poisonous and cynical, but also honest. When the cartel broke up, we learned exactly how great a reporter Reston really was. As a liberal centrist, he had always fared best with handouts from Democrats, but the Nixon establishment had no regard for Team Reston or interest in winning good press from the Times or anybody else--with one exception: Henry Kissinger, whose "manipulations" of fact, as Stacks calls them, the alleged "best reporter in Washington" dutifully and repeatedly published.

Rather than take umbrage, Reston asked Kissinger to write him a dust-jacket blurb for his 1991 memoir. Henry was only too happy to scratch Scotty's back one more time. Small wonder that Reston has been forgotten.