The Lowest Common Denominator: Richard Ben Cramer on the 1988 presidential campaign.

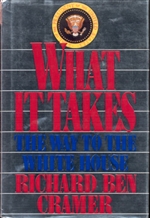

Washington Post, June 28, 1992 Book ReviewsWhat It Takes: The Way to the White House, by Richard Ben Cramer. 1,047 pp. Random House, $28.

Richard Ben Cramer's swift and beautiful barge of a book about the 1988 presidential campaign, What It Takes, answers the question posed by Hunter S. Thompson two decades ago: "How low do you have to stoop in this country to be president?"

Richard Ben Cramer's swift and beautiful barge of a book about the 1988 presidential campaign, What It Takes, answers the question posed by Hunter S. Thompson two decades ago: "How low do you have to stoop in this country to be president?"In the '88 go-round, the campaign trail was swarming with willing stoopers--a former NFL quarterback, a gaggle of governors and senators, a standing veep, a dyspeptic retired general, a lowly representative, and two servants of God. Most of these men had targeted the White House from the beginnings of their careers and were willing to limbo through hell for the prize.

But how low would they go?

"What I wanted, what I could not find, was an account I could understand of how people like us--with dreams and doubts, great talents and ordinary frailties--get to be people like them," Cramer writes in the introduction to his 1,047-page behemoth, which took him longer to write than it takes to run for president. "What happened to their idea of themselves? What did we do to them, on the way to the White House?"

A veteran journalist, Cramer had covered the U.S. Marine deployment in Beirut, a political campaign where the advance men toted rocket grenade-launchers instead of cellular phones. Joining the presidential-campaign cavalcade in 1986, he eventually narrowed his study to six men--Bush, Dole, Dukakis, Gephardt, Hart and Biden--real contenders who readily shared with him their thoughts and passions and pasts and presents. (Jesse Jackson didn't make the book's cut because he wouldn't volunteer the required candor).

The triumph of What It Takes is that it reanimates the candidates who were steamrollered from 3D into 2D by the campaign process. Cramer's extravagant use of exclamation points, ellipses, AND ALL CAPITALS to tell his story will--but shouldn't--invite comparisons to the chronicler of right stuffdom. Like Tom Wolfe, he has gone goofy from prolonged immersion in his subject, and he feels compelled to corrugate the page with fancy punctuation and obscenity.

Bringing the cartoons of Campaign '88 back to life isn't always a pretty sight. Take Dick Gephardt, whose translucence segued into invisibility after a spring 1988 boomlet. Gephardt started his campaign earlier than anyone else, plowing "must-win" Iowa in 1984, delivering so many speeches there that his mouth went dusty with platitudes. Yes, his carefully laid plan to win in Iowa succeeded, but instead of expanding the intellectual content of his pitch for the rest of the country, he shrank it. "I gotta get it down to five words," he said. "Something people can hold onto ..." His pep-club mantra--"It's Your Fight, Too!"--preceded him into oblivion.

Boy wonder Joe Biden painted his presidential campaign by the numbers, giving nobody a good reason to vote for him. A candidate needs an experienced guy to run his campaign, so Biden hired a Kennedy hack. A candidate needs money, so he whored for dough from the Hollywood Women's Political Action Caucus, even though he knew he should be prepping for the first debate. (Don't let anybody tell you Perot is the first to attempt to buy an election.) A candidate must have a pollster, so Biden lined up Pat Caddell, the villainous pro who slouches still for the White House.

Making the obligatory foreign policy speech at Harvard, Biden had stirred all the basic ingredients into the pot except one: Why was he running? "Just a week before the announcement, [Biden] started to mutter aloud about 'the timing' ... 'the feel,' " Cramer writes. "Then Joe mentioned to the new press guy, Larry Rasky, that he thought, well, maybe ... he didn't want to run." When his run was truncated by charges of plagiarism, it worked out for the best. A wicked headache he had been medicating with handfuls of Tylenol finally blew into a life-endangering aneurysm: If he'd been out on the hustings, he'd probably have died.

The subtext of What It Takes is that a candidate must maintain his vigilance lest the handlers (Cramer calls them the "white men") take over. But more than once in What It Takes, the white men save the day. Like most of the other candidates, Dukakis permitted the white men to inspect his personal life for the trapdoors his opponents might spring. Since the voters now believe that they're casting ballots for a First Family, too, the interrogation included the family, and the handlers learned that wife Kitty had been buzzed on crank for 20 years. The specter of a "Kitty Dukakis Speed-Eating Dynamics Course" could have easily scuttled the Dukakis campaign, but the white men staged a weepy public confessional and repackaged her travail to the candidate's benefit.

Had the white men gotten to him in time, Gary Hart might not have snagged his presidential ambitions in his zipper. Hart never bent or sniveled to win the presidency in 1988. Robotic and self-righteous, he even refused to pose for a photograph to illustrate a journalistic profile of him as a candidate. A campaign obsessive, Hart was happiest explaining his Ptolemaic theory of how to win the White House. Build concentric rings--one in each state--of 10 to 12 supporters and instruct each supporter to build another ring of supporters and so on until the pattern ripples out to every voter.

But reanimating Hart is beyond Cramer's talents. He reads like an enigma, lying about his age in the campaign, denying his past, covering up the changing of his name, abandoning his faith and his wife, and ultimately sabotaging his own presidential campaign with the Donna Rice affair. Filling in the Hart emptiness even defeated the inestimable E.J. Dionne, who profiled the candidate for the New York Times during the campaign. Now a reporter for the Washington Post, Dionne grew skittish in his questioning of Hart, Cramer reports, and the candidate asked him what he was looking for. "Why do you think ... that we think ... you're weird?" Dionne said.

Cramer puts the vile and craven campaign techniques of Dole and Bush under the same scrutiny as the Democrats', but he doesn't give them much hell. Perhaps Cramer is infatuated by them because of their war heroics, because he once viewed war from close-up. It's hard not to admire the infantryman Dole, who was mutilated by German bullets and fought his way back from paralysis, or the aviator Bush, who hit the silk and dropped into the Pacific after the Japanese blasted his TBM Avenger out of the sky.

But by book's end, Cramer has convinced the reader that Dole has the manners of a hyena and Bush the scruples of a carnival barker and that winning the presidency requires such a feral personality. If that means stiffing the press, stonewalling on Iran-contra, accusing Dole of financial improprieties, brutalizing Dan Rather on television, making campaign promises he can't deliver ("No new taxes"), then so be it. But the willingness to "do whatever it takes" to win the White House, which is attributed to George Bush again and again as his personal key, will only take you so far. A modern presidential hopeful needs to run again and again. Ronald Reagan didn't win until his third run. George Bush, according to Cramer, coveted a vice presidential nod from Nixon in 1968; he hoped that Agnew would get bumped in 1972 to make room for him; and he hoped that Gerald Ford would appoint him the interim veep in 1974, or at least make him running mate in 1976. Bush groveled early, groveled continuously, and at last report was still groveling for a second term. (Richard Nixon pioneered this strategy: He started running for president in the early '50s and damned if he isn't still running.)

The inchoate message of What It Takes is that none of the post-Depression, post-World War II generation candidates--Biden, Gephardt, Hart and Dukakis--is worthy. Their soft odysseys haven't prepared them for the office. Until you've walked tall, really tall, Cramer implies, you have no right to crawl into the White House.